An exploration of Dutch midwives’ opinion on the implementation of the new policy to enhance the care of pregnant asylum seekers

Moi Thuk Shung e/v Doergaram Tewarie Jenny Rina

MMB722342-15-AB

This dissertation is submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Midwifery from Glasgow Caledonian University

August 2016 of Submission

“This dissertation is my own original work and has not been submitted elsewhere in fulfilment of the requirements of this or any other award. An exact copy of this piece of work has also been submitted to the Dissertation Turnitin site on GCU Learn”

Abstract

Background In February 2014 the Health Care Inspectorate (2014) in the Netherlands announced that in order to improve pregnancy care for pregnant asylum seekers and their children, policies and guidelines had to be adjusted. A literature review of the topic identified a deficit in information relating to the opinions of Dutch midwives using the modified policies and protocols for pregnant asylum seekers in the Netherlands.

Aim This study aims to explore Dutch midwives’ opinion in providing health care to pregnant asylum seekers due to the implemented policies and guidelines.

Methods Purposive sampling from contacted midwifery practitioners and a cross-sectional descriptive approach was used to explore midwives’ opinion in relation to the applied policies and guidelines in providing care to pregnant asylum seekers. Survey Monkey was used to deliver the questionnaires online to the respondents and obtain respondents’ answers to the questionnaires.

Results The opinions of the Dutch midwives concerning the communication processes, the transfer processes, cultural diversity, language barriers and the use of a case manager in providing care to pregnant asylum seekers were largely positive. Contradictions were found in the responses regarding the use of an interpreter service. Conclusively the study revealed that the responders do not seem to make use of the interpreter services.

Conclusion The council of the European Union in Directive 2003/9 / EC of the Council of 27 January 2003 has laid down minimum standards for the reception of asylum seekers. Health care for pregnant asylum seekers was improved by adjusting the policies and guidelines of the mandatory reception regulations for dignified standard of living conditions in the Netherlands. In 2014 The Health Care Inspectorate conducted an extensive serial nationwide multi-annual study of prenatal, natal and postnatal care. This study aims to find out whether there are significant improvements to be made by modifying the maternity policies and guidelines. This is done by exploring Dutch midwives’ opinion on the implementation of the new policy to enhance the care of pregnant asylum seekers.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported with funding completely by the author who undertook the study. This study was self-funded by the author.

The author reports no conflicts of interest in this work.

This Research Dissertation owes much to the people who guided and supported me along the way. Thanks to:

Family Doergaram Tewarie, support and patience,

Mrs. Catriona Hendry, midwifery lecturer at Glasgow Caledonian University,

Mrs. Dr. Marion Welsh, senior lecturer in Research Methods teaching at Glasgow Caledonian University,

Mrs. Linda Evans, bilingual support,

Mr. Herman Braat, de Datawerkplaats: statistics support.

Introduction

There is growing international attention on migrant health, reflecting the recognition of the need for health systems to adapt to the increasingly diverse populations (WHO, 1978). That is not surprising, according to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), head of the refugee agency of the United Nations. The UNHCR reveals that the Member States of the European Union (EU) registered 570,800 asylum claims in 2014, a 44 per cent increase compared with 2013 (396,700). The EU states together accounted for 80 per cent of all new asylum claims in Europe. The Netherlands accounted for five per cent (29,890) of the EU registered asylum claims in 2014 and four per cent (17,189) in 2013 (UNHCR, 2016). In 2007 the EU Presidency made migrant health a priority, resulting in a statement by the EU Council of Ministers, while further support came from the Council of Europe in the 2007 Bratislava Declaration on Health, Human Rights and Migration and the 2008 World Health Assembly resolution on the Health of Migrants (Rechel, 2011). The study by Rechel et al. 2012 points out that the health data of migrants are crucial for providing appropriate and accessible health service to this expanding group of people. There seems to be a lack of information on the health of migrants, which limits possibilities for monitoring and improving migrant health. Yet, the European Parliament and the Council of the European Union who announced a programme of community action on health monitoring in 2008 the Euro-Peristat (Peristat) revealed the first European health report (European Communities, 2001; Peristat 2008). The Peristat 2008 reveals health indicators to monitor the quality of pregnancy care in Europe; for a high-income industrial country, the Netherlands stands out with regard to adverse pregnancy outcomes in comparison with the other European countries as a result of the Peristat reports. Moreover, two cohort studies in the Netherlands provided more detailed information about the poor performance according to the Peristat report (Troe et al., 2007; Goedhart et al., 2008). Both studies revealed that adverse pregnancy outcomes in the Netherlands were mainly observed among the ethnic minority groups, with an emphasis on the subgroup of asylum seekers, in comparison with the native Dutch pregnancy outcomes.

Goedhart et al. 2008, Table 1. Prevalence rates of total PTB, SPB and IPB per ethnic group

PTB: Preterm birth

SPB: spontaneous preterm birth

IPB: iatrogenic (medically indicated) preterm birth

| Ethnicity |

Number of women |

Total PTB (n) |

Total PTB (%) |

SPB, n (% of PTB)* |

IPB |

Unknown subtype, n (% of PTB)* |

| Induction, n (% of PTB)* |

Primary section, n (% of PTB)* |

| Dutch |

4099 |

209 |

5.1 |

159 (76.1) |

10 (4.8) |

26 (12.4) |

14 (6.7) |

| Surinamese |

608 |

56 |

9.2 |

35 (62.5) |

7 (12.5) |

6 (10.7) |

8 (14.3) |

| Antillean |

114 |

10 |

8.8 |

5 (50.0) |

2 (20.0) |

2 (20.0) |

1 (10.0) |

| Turkish |

380 |

19 |

5.0 |

14 (73.7) |

2 (10.5) |

0 (0) |

3 (15.8) |

| Moroccan |

661 |

27 |

4.1 |

11 (40.7) |

0 (0) |

4 (14.8) |

12 (44.4) |

| Ghanaian |

155 |

17 |

11.0 |

7 (41.2) |

2 (11.8) |

3 (17.7) |

5 (29.4) |

| Other non-Dutch |

1587 |

79 |

5.0 |

52 (65.8) |

7 (8.9) |

12 (15.2) |

8 (10.1) |

| Total |

7604 |

417 |

5.5 |

283 (67.9) |

30 (7.2) |

53 (12.7) |

51 (12.2) |

Asylum seekers are regarded as a vulnerable group by the UNHCR (UNHCR, 2014). The World Health Organisation (WHO) argued in early 2000 that there should be appropriate health care for all (Baum, 2007). One of the key elements was the achievement of equality in health status for vulnerable populations throughout the world (WHO, 1978). This statement means equality for people in terms of health status by means of providing the best health care available (Evans et al., 2001), as members of the international community the Dutch midwifery and obstetrical care society state their concerns regarding vulnerable pregnant women in the Netherlands (Altink et al., 2014; Midwifery in the Netherlands, 2014; NVOG, 2014). Their concerns focus on the pregnant asylum seekers because of the increased adverse pregnancy outcome regarding maternal and foetal morbidity and mortality (Goosen et al., 2010; Oostrum et al., 2011; Hanegem et al., 2011; Hayes et al., 2011). The healthcare issues surrounding the pregnant asylum seekers attracted the attention of politicians and as a result the government altered the policies and guidelines for the (pregnant) asylum seeker. The Directive 2003/9 / EC of the Council of 27 January 2003 which laid down minimum standards for the reception of asylum seekers, was improved with the mandatory reception regulations for a dignified standard of living conditions for (pregnant) asylum seekers (Eerste Kamer der Staten-Generaal, 2016).

The Central Agency for the Reception of Asylum Seekers, COA, is the organisation that provides hosting for the asylum seekers in the Netherlands (COA, 2014).

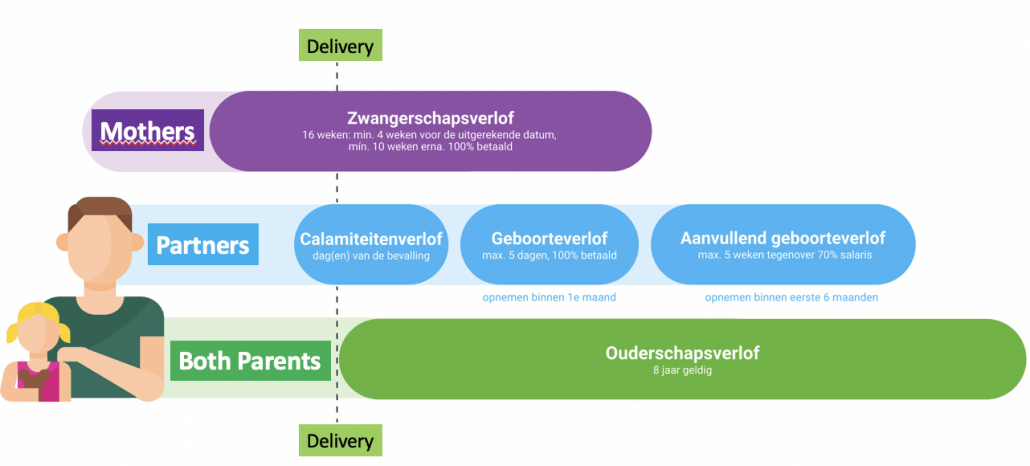

The COA outsourced the total asylum seekers’ health care requests to the Mensis-COA-Administrative MCA. The MCA is responsible for providing all layers of healthcare in terms of accessible, available and high-quality primary care for (pregnant) asylum seekers (MCA, 2014). This high-quality health care product is possible due to the governmental action articulated through the act regulating health care for asylum seekers Regeling Zorg Asielzoekers (RZA) (RZA, 2009). This RZA regulates all health care, which the asylum seekers are entitled to and enables them to meet their health care needs. The care for pregnant asylum seekers needs to consist of standard maternity midwifery care, and if appropriate, a referral to obstetrical care. High-risk pregnant asylum seekers’ health care needs to equal the obstetrical care provided to the native Dutch population.

In February 2014 the Health Care Inspectorate communicated that it was conducting a serial extensive nationwide multi-annual study of prenatal, natal and postnatal care in the Netherlands, with a particular focus on the vulnerable pregnant groups. The findings of the study indicate that the adverse pregnancy outcomes among pregnant asylum seekers were reduced (The Health Care Inspectorate, 2014).

This led to the statement of the Inspectorate that inter alia, referrals to hospitals and the use of professional interpreters would generate better maternity care for pregnant asylum seekers (The Health Care Inspectorate, 2014). According to the Inspectorate there are still health benefits to achieve in the health care of pregnant asylum seekers, despite the reduction in negative outcomes.

According to Rees (2011), in the midwifery care domain it is relevant and even necessary to work according to the principles of the Evidence Based Practice (EBP), paradigm, for example, it is essential to evaluate the practice (Lawless et al., 2014). However, there is little literature that describes and evaluates the care management through adjusted obstetrical policies and guidelines and how they are put into practice in the Netherlands with regard to pregnant asylum seekers. This study therefore aims to examine the views of midwives involved in the provision of maternity care for asylum seekers in relation to the current, recommended standards of care.

Literature review

Introduction

Maternal mortality and severe morbidity generally occur more frequently among migrants compared to host populations. In the Netherlands, political efforts have been made to reduce adverse pregnant asylum seekers outcome by adjust policies and guidelines. Therefore, reviewing national and international literature offers in-depth understanding of the topic.

Search strategy

A literature review was conducted from primary and secondary resources in order to understand the topic (Krainovich-Miller et al., 2009; McKibbon & Marks, 1998). Information was retrieved from a wide variety of sources, including journals, articles, books, grey literature, and encyclopaedias using predetermined keywords (derived from the research question) – midwives, asylum seekers, migrants, experience, opinion, policies and guidelines and synonyms (Craig & Smyth, 2012; Krainovich-Miller et al., 2009). Searches were carried out by using CINAHL and Medline (via EBSCOhost) and Pubmed from 2000-2016. The search engine supports gathering existing reliable information on a topic, which can be found in various resources in a structured manner. The findings of the search can be organised in a Prisma flow diagram (See Appendix 6). The researched literature was critically evaluated by use of the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) to ascertain relevant insights about the study topic (CASP, 2013). By critically assessing the literature on the topic, this study aims to ascertain that the retrieved literature is significant and relevant. Furthermore, it was possible to establish whether there is a gap in the knowledge on the study topic within the literature. If the information was found to be appropriate, it was included as study data. Grey literature was processed with the same approach.

The Key Themes

As mentioned, reviewing national and international literature offers in-depth understanding of the topic. This is achieved by using key themes associated with adverse pregnancy outcome among asylum seekers.

A study by Correa-Velez and Ryan (2012) was included because it attempted to identify key elements that characterise the best practice model of maternity care for women who have an asylum-seeker background. It was identified that factors such as high-quality interpreter services, education strategies for healthcare qualified personnel and pregnant women, and the continuity of qualified health care providers were essential (Correa-Velez & Ryan, 2012). Several authors provided similar findings (Kurth et al., 2010; Merry et al., 2011; Hanegem et al., 2012), which suggest a certain consensus regarding key elements in asylum seekers’ health care. Correa-Velez & Ryan (2012) conducted a multifaceted project in Australia that included a literature review, consultations with key stakeholders, a chart audit of hospital use by African-born women in 2006 that included their obstetric outcomes, a survey of 23 African-born women who gave birth at a hospital in 2007–08, and a survey of 168 hospital staff members. This provided the study with an effective population frame to conduct a high-quality study (Gage & Norton, 2012). Yet, communication barrier is a key element that studies do not address; this difficulty affects patients as well as care providers. Furthermore, Rodrique et al. (2010) suggest that health activities should be guided by protocols.

According to Rodrique et al. (2010) activities are based on protocols, which is a complex issue. It is essential that health professionals are familiar with the recommended guidelines for good practice. Similarly, he argues that the awareness of the health professional on the protocols (adjust as needed) is the next step, which must be followed by reflection on the applied guidelines (Rodrique et al., 2010).

Moreover, Akavan (2012) highlights the importance of communication barriers as an obstacle to the provision of appropriate care.

The study outcome Akavan (2012) revealed that communication barriers were one of the main parameters, which led to unequal care between native Swedes and asylum seekers. This qualitative study was undertaken to understand the midwives’ views on inequalities due to immigrants’ status. Ten midwives of units in two municipalities with experience in providing care for asylum seekers were questioned in semi-structured interviews (Akavan, 2012). The study findings were transcribed and related categories were identified through content analysis.

The findings of these studies are further supported by a more recent qualitative study by Tobin and Murphy-Lawless (2014) who undertook an in-depth unstructured interview approach to explore the midwives’ experiences in providing care to asylum seekers. A purposive sample of ten midwives was drawn from two sites. Both sites are teaching hospitals with similar birth rates in excess of 9,000 per year. For a qualitative study, the sample of ten midwives appears acceptable, especially taken in to account the numbers of birth attended. The midwives were able to indicate based on their day-to-day experience which challenges they encounter while providing care to pregnant asylum seekers. Results were, for example, barriers to communication, understanding cultural differences, challenges caring for asylum seekers, emotional cost of caring and structural barriers to effective care (such as policies and protocols).

Knowledge gaps

Communication Barrier: Several Dutch studies indicated that the communication barrier due to poor language skills fostered adverse pregnancy outcomes. This especially seems to be the case for vulnerable pregnant women and their children, which includes pregnant asylum seekers. Alderliesten et al. (2007) in their study observed a delay by all ethnic groups, among them asylum seekers, in visiting an obstetrical health care professional for their first consultation. The study explained the findings by a high prevalence of the identified risk factor of poor Dutch language skills. The assumption is made by the study that poor skills in Dutch lead to disadvantages in acquiring essential information regarding different issues during pregnancy. The study by Hanegem et al. (2011) focused on the severe acute maternal morbidity (SAMM) risk factors for asylum seekers. The study included the entire population of pregnant asylum seekers from 98 maternity units in the Netherlands during a two-year timeframe, conducted through a prospective cohort perspective. The study revealed that one of the most important risk factors was the language barrier. Poor communication skills could influence the care process itself and the communication with the care provider. In addition to language and communication issues, problems associated with transfer of women with obstetric problems appeared to be an issue.

Transferral: Jong et al. (2014) conducted qualitative, semi-structured interviews with pregnant women to discover transfer challenges from a pregnant woman’s point of view. Participants came from different independent midwifery practices located in rural and urban areas. Participants reflected on the challenges they encountered during transfers. Study findings indicated that in some cases the participants experienced a feeling of fear. Others indicated that at times in the process of being transferred they felt confused and did not know what was happing. Overall the participants’ answers demonstrated that during the process of being transferred informational continuity and management continuity were highly valued. It was important for participants that professionals were aware of their medical situation and knew about their personal preferences. Participants indicated that they sometimes had the feeling that information got lost between providers from primary and secondary care during the transfer process. When study participants expressed their need for management continuity, they were referring to consistency and a coherent approach during the transfer from primary to secondary care. Women expressed that the midwife should accompany this transfer, and the midwife should stay until the woman has settled and trusted the secondary provider. The study does not distinguish between ethnicity of vulnerable groups, but only between the experiences of participants. This can be seen as a limitation, nevertheless it can be said that the study revealed (universal) findings that will be even more applicable to vulnerable groups, such as pregnant asylum seekers. Although this was a small qualitative study with limited generalizability, the larger quantitative study by Jans et al. (2015) supports the idea of women having a strong preference for continuity of care and carer. Jans et al.’s (2015) study population included 600 patient records from pregnant women who were referred during labour from primary to secondary care. The main reason for the transferral was the request for pain relief, which accounted for 31% of the total transfers, whereas 60% of the total transferrals required an intervention with additional pain relief. The study findings suggest that primary care midwives should be enabled to give continuity of care to a large group of women transferred from primary care to secondary care with a moderate risk profile. The study findings distinguish between moderate risk factors such as pain relief, meconium, prolonged first stage delivery, prolonged rupture of the membranes, prolonged second delivery stage and a high-risk profile (Jans et al., 2014). According to study findings in the Netherlands, all women who are transferred to obstetricians’ lead care are considered to have a high-risk profile. Conclusively the study points out that a moderate risk profile should be carried out by a midwife to maintain continuity of care during the transfer.

Care management: Alderliesten et al. (2007) comment that several strategies have been developed for the non-native Dutch speaking minorities. One of those alternatives is the implementation and routine use of interpreter services during consultation, in order to enhance the positive outcomes of pregnancies for these minorities. Akker et al. (2016) highlight that substandard care due to delays either by the patient or the health provider are frequent occurrences in the Netherlands. These findings were the result of a quantitative literature search, and showed that there is detailed evidence that emergency care delivered in refugee camps is of a higher standard than care delivered within the local health system. According to Akker et al. (2016) the reasons for this lie in the non-governmental organisations’ efforts to provide refugee camps with the best possible health care. A reference is made to the detailed evidence that pregnancy outcomes in refugee camps are often better than those of the local host population. The study findings reveal that a substantial part of the increased adverse health outcomes must be attributed to the suboptimal health care delivery in for instance the Netherlands. In the Netherlands suboptimal care was more frequently identified in cases of adverse maternal outcomes for non-natives when compared with Dutch natives. Some care is indicated while these study findings are dated 2016 based on empirical data from the first decade of 2000.

Conclusively, Akker et al. (2016) propose that non-native women require increased care during pregnancy and childbirth, which they are entitled to under the principle of universal access of care, to prevent adverse pregnancy outcomes.

Akker et al. (2016): Table 4.

SAMM and ethnic disparity: RR or OR of risk in migrants versus native-born women.

| Country/year |

Maternities |

Number of SAMM/near-miss |

RR or OR |

| Netherlands, 2004–2006 [3] |

358,874 |

2506 |

RR 1.3 (1.2–1.5) |

| United Kingdom 2005–2006 [64] |

775,186 |

686 |

RR 1.58 (1.33–1.87) |

| Australia (Victoria) 2001–2010 [19] |

636,042 |

1316 |

OR 2.0 (1.45–2.75) |

| Canada (Ontario) 2001–2010 [19] |

1.050,688 |

3062 |

OR 1.5 (1.21–1.85) |

| Denmark 2001–2010 [19] |

636,177 |

3085 |

OR 1.8 (1.4–2.21) |

| Sweden 1998–2007 [20] |

914,474 |

2655 |

OR 2.3 (1.9–2.8) |

Case manager: Perdok et al. (2016) studied the opinions of maternity care professionals and other stakeholders in the Netherlands by using a qualitative design, using the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research checklist to study the data. The data revealed that most of the participants believed that client-centred care is a prerequisite for optimal care. In order to reach this goal, one of the issues is to link the collaboration between primary and secondary care to ensure the continuity of care. An alternative model of continuity of care could be a model where the midwife shifts from primary to secondary care in order to ensure the continuity of care. This can be visualised in cases of birth situations which start in primary care and transfer to secondary care while accompanied by the midwife who is the case manager. As this is the envisioned situation for the native pregnant population, asylum seekers should be treated in the same way (Perdok et al., 2016). However, study of the limited material shows that this vision is not widely spread or supported by policies and guidelines. The continuity of care methodology is supported by the majority of health providers and stakeholders; where the frequently mentioned model is that of the case manager (Erwich et al., 2015; Haaren-ten Haken et al., 2014; Hesselink & Harting, 2011). Erwich et al. (2015) used a qualitative study with purposive sampling to select potential practices. The study results, a total of 3,499 answers, were analysed using the software program Max Qualitative Data Analysis. The study findings recognised individualised care for pregnant women as a key element. Other findings from the study listed additional provider and service characteristics as further elements of advanced health care for mother and child. The provider characteristics were specified in elements such as interpersonal skills, i.e. the interactions with the client and others involved. Communication was another element that was specified as communication skills and information provision. The service characteristics were further divided into additional or adjusted care, assistance and support, time spent with client, continuity of care provider, continuity of care, and accessibility. The themes identified in the study are supported by national and international studies.

Factors associated with ethnicity: A nationwide confidential study into the causes of maternal mortality by Graaf et al. (2012) aimed to study regional differences in maternal mortality ratio (MMR) in the Netherlands. As the study unfolded they learned that non-Western pregnant women suffered an excess risk of MMR, which is the number of maternal deaths during a given period of time per 100,000 live births in the same period of time; this excess risk was also echoed by numerous European studies. Beside the lack of proper skills in Dutch, additional risk factors were found in inefficient pregnancy consultations, such as irregular consultation due to different causes.

Study justification

Since 2012 the Dutch authorities have focused on pregnancy healthcare for asylum seekers, with special emphasis on communication, referrals and documentation (The Health Care Inspectorate, 2014). The Health Care Inspectorate (2014) has announced that communication and referrals in health care need to be adjusted to provide responsible birth care for asylum seekers. In conclusion, the adjusted guidelines need another review and adjustment. Little information is available regarding the opinion of midwives working with the adjusted policy and guidelines while caring for pregnant asylum seekers. A search of the literature databases failed to find Dutch literature on the subject, and only a small number of studies that focused on asylum seekers. Moreover, no Dutch literature was found that studied the opinion of midwives working with the adjusted policy and guidelines while caring for pregnant asylum seekers. In the study by Akker et al. (2016) concerns were communicated regarding a possible reduction in access to interpreter services due to political anti-immigrant pressure, which could increase the communication barrier between non-natives (including asylum seekers) and health workers.

Short conclusion

The aim of this study is to explore the opinions of midwives in the Netherlands regarding the newly implemented policy and guidelines that are applicable to pregnant asylum seekers. In addition, it seeks to gain insight of midwives’ opinions regarding policy implementation to foster practice development.

Conclusion and recommendations

Conclusion

communication

Based on the analysed data it appears that the midwives who participated in the study respect the ruling policies and guidelines by practising them while providing health care to low-risk pregnant asylum seekers. These policies and guidelines are attached to the contract that independent midwifery practices have to sign if they want to provide health care to low-risk pregnant asylum seekers in the Netherlands.

The midwife respondents demonstrated a critical attitude through reflections on the adapted policies and guidelines while working with those that are used inter alia in independent midwife practices.

The issue that has been identified as strongly related to the less positive pregnancy outcomes among asylum seekers is the communication barrier, something that is frequently echoed in literature. The solutions regarding the communication barrier are diverse and are often reduced by using an interpreter to overcome problems. According to the policies and guidelines, midwifery practices are obliged to work with an interpreter for each consultation with a pregnant asylum seeker whenever there is a communication barrier. However, this is not done on a day-to-day basis. In this study 70 percent of the responders revealed that during the entire pregnancy there is a lack of interpreter services. In addition, that tells us that 30 percent of the respondents optimise the communication by using the interpreter service. The respondents from the midwifery organisations implied that relatively little use is made of the interpreter service in relation to the mandatory policies and high accessibility of the interpreter service. The underlining reasons for the experienced discrepancy are unclear and not revealed by the study data.

To summarise, study findings indicate that interpreter services are not being used to their full capacity, although the participating midwives agreed regarding the usefulness of decreasing communication barriers through an interpreter. Why the midwives use the interpreter services the way they do, is not answered or concluded in this study.

Transferral

The transferral (COA to the first line health provider (hp)); first line hp to the first line hp; first line hp to the second line hp) of prenatal, natal and postnatal care in cases of low-risk pregnant asylum seekers is viewed by the respondents as adequate and effective. The midwives indicated that the independent midwifery practices acted as the referring body in most of the cases. This is a consequence of the Dutch midwifery organisation, where midwives as primary care providers initially stand at the front of the health care system in the Netherlands. The Dutch midwiferies perform as gatekeepers of the transferral for low-risk pregnancy through the health care system in low-risk pregnancies.

The midwife can refer a low-risk pregnant woman to a second health care service if she decides that the woman no longer fulfils the criteria for a low-risk profile due to her care or health profile. This decision can be made during the first thorough consultation or later on in the care process.

The respondents’ opinion regarding the transferral through the health care system received an 80 to 90 percent score for correct standard care. Less than 20 percent of the respondents seem to consider the transferrals as inferior care. The study findings cannot define the reason for the 20 percent inferior transferral care.

To summarise: study findings indicate that midwife respondents consider low-risk asylum seekers’ pregnancy as correct transferral standard care. A small percentage of respondents, 20 percent, is of a different opinion. It was not in the study focus to reveal the underlying reasons.

Experience / management

Case management

The respondent midwives reviewed the quality of the Dutch obstetric care regulated by guidelines and policies for the low-risk population pregnant women as follows: The care is equal for pregnant asylum seekers and the Dutch native population according to 70 percent of the midwives.

In this interpretation a deviant of 30 percent believe that the quality of obstetric care for pregnant asylum seekers is not good enough based on the equivalence principle.

The quality of care management for low-risk pregnant asylum seekers is rated by 60 percent of the respondents to be equal to the care management for the Dutch native population. 40 percent of the midwives believe that while Dutch legal regulations are in place, care management on local level can be improved to optimise healthcare for low-risk pregnant asylum seekers. The issues or deficits that should be addressed to achieve a higher efficiency rate of care management for low-risk pregnant asylum seekers are not revealed through the study data.

To summarise: the findings of the study indicate that there are shortcomings observed by the responding midwives. These shortcomings are detected by the obstetrical care as well by the obstetrical management based on the principle of equality. Where those shortcomings are being observed, felt and reflected upon is not answered through this study.

Case manager

The responding midwives’ opinion of the use of a case manager to benefit pregnancy health care for asylum seekers scored 80 percent positive answers. The remaining 20 percent of the respondents did not support the majority’s opinion. The study’s focus was not to identify the reason for those 20 percent deviation and hence cannot identity the reason for it.

To summarise: the findings of the study indicate that the majority of the midwife respondents are very positive about using the concept of a case manager in the pregnancy care of asylum seekers. A small percentage of respondents, 20 percent, is of a different opinion. It was not in this studs focus to reveal the underlying reasons.

Factors associated with ethnicity

The concept of managing health care outcome by using a case manager during fixed consultations, and especially in particular obstetrical situations, is reflected upon with a score of 80 to 90 percent by the respondents. The dissent opinion of the remaining 20-10 percent is not disclosed within this study because of the focus of the study.

To summarise: The vast majority of respondents in the study indicated that the concept of a case manager on fixed consultation in health care situations by pregnant asylum seekers will have a positive influence on the obstetrical health outcome for mother and child. A minor percentage of respondents, 20- 10 percent, is of a different opinion. It was not in this study’s focus to reveal the underlying reasons.

Study limitations

Study results need to be interpreted in light of some limitations, whereas the main limitation lies in the nature of the sample. The recruitment of participating midwifery organisations was done by using the health care contracts from the insurance companies that are responsible for the health care accessibility of asylum seekers. The regulations require that a midwifery organisation can acquire a contract, as opposed to an individual practising midwife. As a consequence, the study population consists of independent midwifery practices. The owners of an independent midwifery practice do not have a mandatory requirement to communicate their legal entity to third parties. Additionally, they do not have to communicate how many co-workers they employ at any time. In conclusion, the recruitment of participating midwifery organisations was best answered by the concept of probability selection of participants, which included all independent midwifery practices able to deliver health care to asylum seekers in the Netherlands. Response rates cannot be calculated due to lack of precise information about the number of individuals in all independent midwifery practice organisations who received an invitation to participate.

The study findings were from a sample population, which is equal to the entire population. All independent midwifery practices with a healthcare contract for asylum seekers received the study questionnaire. The entire population contains 120 midwifery organisations with a return reaction of 34 (28%) responses, with 29 (24%) being fully completed. Because of the relatively low figures the study data were organised and combined to relevant parameter values. The results were presented in clear tables, graphs and figures, such as histograms, bar and line charts.

Inductive statistics through SPSS have not been used as the principle of predictions, estimations, testing hypotheses and deriving estimates about a population from data sampled from that population are not applicable to the study data. Despite the absolute small number of replies, but relatively large population, generalisations could be made because of the nature of the study population.

Implications and recommendations

There are currently limited data on the perspectives of midwives who provide care to childbearing women while they are in the process of seeking asylum. The aim of the study was to review the extent of implementation adjusted policies and guidelines as these guidelines are in the process of being tightened again. Study findings revealed that the participating midwives for the vast majority seemed to work correctly and timely according to the policies and guidelines. The results from the study suggest the need to investigate an in-depth opinion perspective by performing a qualitative study to discover the relatively low percentage of deviating findings.

Reference

Akker, van den T. & van Roosmalen, J., 2016. Maternal mortality and severe morbidity in a migration perspective. Best Practice & Research Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology [online], 32, pp.26-38. [viewed 30 June 2016]. Available from: http://www.sciencedirect.com.gcu.idm.oclc.org/science/article/pii/S1521693415001601

Alderliesten, Vrijkotte, Wal, v. d., & Bonsel, 2007. Late start of antenatal care among ethnic minorities in a large cohort of pregnant women. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology [online], 114(10), pp.1232-1239. [viewed 30 June 2016]. Available from:

http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com.gcu.idm.oclc.org/doi/10.1111/j.1471-0528.2007.01438.x/full

Akhavan, S., 2012. Midwives’ views on factors that contribute to health care inequalities among immigrants in Sweden: a qualitative study. International Journal for Equity in Health [online]. 11. [viewed 20 July 2015]. Available at: http://www.equityhealthj.com/content/11/1/47

Aitink, M., Goodarzi, B. & Martijn, L., 2015. “Voor continuiteit en kwaliteit Beroepsprofiel van de verloskundige [online]. Ovimex Grafische Bedrijven Deventere. [viewed 2 July 2016]. Available at:

http://www.knov.nl/fms/file/knov.nl/knov_downloads/1866/file/Beroepsprofiel_verloskundige_vastgesteld_in_ALV_juni_2014_(1).pdf?download_category=overign

Baum, F., 2007. “Health for All Now! Reviving the spirit of Alma Ata in the twenty-first century: an Introduction to the Alma Ata Declaration’. Soc. Med. [online]. 2(1), pp.34-41. [viewed 29 November 2014]. Available at:

http://www.socialmedicine.info/index.php/socialmedicine/article/view/76/187

Blair, M., 2011. Lessons Learned From Translators and Interpreters From the Dinka Tribe of Southern Sudan, J Transcult Nurs. [online]. 22(2) pp. 116-121. [viewed 07 June 2016]. Available at: http://tcn.sagepub.com.gcu.idm.oclc.org/content/22/2/116.long

Beckman, L., & Earthman, C., 2010. “Developing the Research Question and Study Design”. Support Line [online]. 32(1), pp. 3-7. [viewed 23 October 2014]. Available at: http://search.proquest.com.gcu.idm.oclc.org/docview/228273296?pq-origsite=summon

Bouchghoul, H., Hornez, E., Duval‐Arnould, X., Philippe, H., & Nizard, J., 2015. Humanitarian obstetric care for refugees of the syrian war, the first 6 months of experience of gynécologie sans frontières in zaatari refugee camp (jordan). Acta Obstetricia Et Gynecologica Scandinavica [online]. 94(7), pp. 755-759. [viewed 25 June 2016]. Available at: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com.gcu.idm.oclc.org/doi/10.1111/aogs.12638/epdf.

Bowling, A. & Ebrahim, S., 2005. Handbook of Health Research Methods [online]. Open University Press. [viewed 23 October 2014]. Available at: https://www.dawsonera.com/readonline/9780335224364

Burchett, H., & Bragg, R., 2010. Pregnant asylum seekers. British Medical Journal [online]. 341(7771), pp. 472-472. [viewed 30 June 2016]. Available at: http://www.jstor.org.gcu.idm.oclc.org/stable/20766260

Byrskog, U., Olsson, P., Essén, B. & Allvin, M.K., 2015. Being a bridge: Swedish antenatal care midwives’ encounters with Somali-born women and questions of violence; a qualitative study. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth [online]. 15(1). [viewed 25 June 2016]. Available at:

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4299129/pdf/12884_2015_Article_429.pdf

CAPS Critical Appraisal Skills Programme, 2013. [online]. [viewed 20 May 2016]. Available at:

http://www.systematicreviewsjournal.com/content/supplementary/2046-4053-3-139-s8.pdf

Central Committee on Research Involving Human Subjects CCMO, 2014. [online]. [viewed 6 December 2014]. Available at: http://www.ccmo.nl/en/

Carolan, M., 2010. Pregnancy health status of sub-Saharan refugee women who have resettled in developed countries: a review of the literature. Midwifery [online]. 26(4), pp. 407–414. [viewed 30 June 2016]. Available at: http://www.sciencedirect.com.gcu.idm.oclc.org/science/article/pii/S0266613808001083

Central Committee on Research Involving Human Subjects CCMO. 2014, [online]. [viewed 6 December 2014]. Available at: http://www.ccmo.nl/en/

COA The Central Agency for the Reception of Asylum Seekers, 2016. [online]. [viewed 30 June 2016]. Available from: http://www.coa.nl/en/

Couper, M.P., 2000. Web-based surveys: A review of issues and approaches. Public Opinion Quarterly [online] 64(4), pp. 464– 494. [viewed 20 July 2015]. Available at: http://www.jstor.org.gcu.idm.oclc.org/stable/3078739?seq=3#page_scan_tab_contents

Correa-Velez, I. & Ryan, J., 2012. “Developing a best practice model of refugee maternity care”. Women and Birth [online], 25(1), pp. 13 – 22. [viewed 31 October 2014]. Available at:

http://www.sciencedirect.com.gcu.idm.oclc.org/science/article/pii/S1871519211000199

Craig, J.V. & Smyth, S.L., 2012. The evidence-based practice manual for nurses [online]. 3rd ed. Churchill Livingstone, New York, Edinburgh. [viewed October 28 November 2014]. Available at: https://www.dawsonera.com/readonline/9780702046681

Eerste Kamer der Staten-Generaal: document Europese Commissie, 2011. [online]. [viewed 01 June 2016]. Available at: https://www.eerstekamer.nl/eu/edossier/e110028_herzien_voorstel_voor_de

Erwich, J., Jaap H. M, Baas, C. I., Wiegers, T. A., de Cock, T. P. & Hutton, E. K., 2015. Women’s suggestions for improving midwifery care in the Netherlands. Birth-Issues in Perinatal Care [online]. 42(4), pp.369-378. [viewed 30 June 2016]. Available from: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com.gcu.idm.oclc.org/doi/10.1111/birt.12185/epdf

European Communities 2001: Decision no 521/2001/ec of the Europeaan Parliament and of the council 2001 [online], [viewed 01 June 2016]. Available at: http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=OJ:L:2001:079:0001:0007:EN:PDF

EURO-PERISTAT Peristat 2008, “European Perinatal Health Report” [online]. SCPE, EUROCAT & EURONEOSTAT. [viewed 01 June 2016]. Available at:

http://www.google.nl/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=2&ved=0CCsQFjAB&url=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.perinataleaudit.nl%2Fdownloads%2Fbestand%2F649%2Fperistat-ii-2008-&ei=N6eqVO_iIdXlas_IgqAI&usg=AFQjCNHy8VYDjkhWRz5ZjjOxvyxgnuv0VQ&sig2=a1AMqZnyjojjIQi1vgeW-w&bvm=bv.82001339,d.d2s

Evans, T., Whitehead, M., Diderichsen, F., Bhuiya, A. & Wirth, M., 2001. “Challenging Inequities in Health: From Ethics to Action” [online]. Oxford University Press. [viewed 28 November 2014]. Available at: http://www.oxfordscholarship.com.gcu.idm.oclc.org/view/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195137408.001.0001/acprof-9780195137408

Gerrish, K. & Lacey, A., 2010. The Research Process in Nursing [online]. 6th ed. Wiley-Blackwell, [viewed 5 December 2014]. Available at: https://www.dawsonera.com/readonline/9781118682104

Federation of Physical Medicine Scientific Societies FMWV, 2014. [online]. [viewed 28 December 2014]. Available at: http://www.federa.org/code-goed-gedrag

Gage, W. & Norton, C., 2012. “Measuring quality in nursing and midwifery practice”. Nursing Standard [online]. 26(45), pp. 35-40. [Accessed 1 January 2015]. Available at: http://search.proquest.com.gcu.idm.oclc.org/docview/1026850027?pq-origsite=summon

Goedhart, G., Eijsden, M., Wal, M.F. & Bonsel, G.J., 2008. “Ethnic differences in preterm birth and its subtypes: the effect of a cumulative risk profile”. Bangladesh Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology [online]. 115(6), pp. 710-719. [viewed 1 June 2016] Available at: http://su3pq4eq3l.search.serialssolutions.com/?ctx_ver=Z39.88-2004&ctx_enc=info%3Aofi%2Fenc%3AUTF-8&rfr_id=info:sid/summon.serialssolutions.com&rft_val_fmt=info:ofi/fmt:kev:mtx:journal&rft.genre=article&rft.atitle=Ethnic+differences+in+preterm+birth+and+its+subtypes%3A+the+effect+of+a+cumulative+risk+profile&rft.jtitle=BJOG+%3A+an+international+journal+of+obstetrics+and+gynaecology&rft.au=Goedhart%2C+G&rft.au=van+Eijsden%2C+M&rft.au=van+der+Wal%2C+M+F&rft.au=Bonsel%2C+G+J&rft.date=2008-05-01&rft.eissn=1471-0528&rft.volume=115&rft.issue=6&rft.spage=710&rft_id=info:pmid/18410654&rft.externalDocID=18410654¶mdict=en-US

Graaf, van J., Schutte, J., Poeran, J., van Roosmalen, J., Bonsel, G. & Steegers, E., 2012. Regional differences in Dutch maternal mortality: Regional differences in maternal mortality. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology [online]. 11(5), pp. 582-588. [viewed 30 June 2016]. Available from: http://su3pq4eq3l.search.serialssolutions.com/?ctx_ver=Z39.88-2004&ctx_enc=info%3Aofi%2Fenc%3AUTF-8&rfr_id=info%3Asid%2Fsummon.serialssolutions.com&rft_val_fmt=info%3Aofi%2Ffmt%3Akev%3Amtx%3Ajournal&rft.genre=article&rft.atitle=Regional+differences+in+Dutch+maternal+mortality&rft.jtitle=BJOG%3A+An+International+Journal+of+Obstetrics+%26+Gynaecology&rft.au=de+Graaf%2C+JP&rft.au=Schutte%2C+JM&rft.au=Poeran%2C+JJ&rft.au=van+Roosmalen%2C+J&rft.date=2012-04-01&rft.issn=1470-0328&rft.eissn=1471-0528&rft.volume=119&rft.issue=5&rft.spage=582&rft.epage=588&rft_id=info:doi/10.1111%2Fj.1471-0528.2012.03283.x&rft.externalDBID=n%2Fa&rft.externalDocID=10_1111_j_1471_0528_2012_03283_x¶mdict=en-US

Goosen, S., Oostrum, van, I.E. & Essink-Bot, M.L., 2010. ‘ Obstetric outcomes and expressed health needs of pregnant asylum seekers: a literature survey”. Ned. Tijdschr. Geneeskd., [online]. 154(47). [viewed 29 November 2014]. Avialable at: http://www.ntvg.nl/artikelen/zwangerschapsuitkomsten-en-zorgbehoeften-bij-asielzoeksters/volledig.

Haaren‐ten Haken, T., Pavlova, M., Hendrix, M., Nieuwenhuijze, M., Vries, R. & Nijhuis, J., 2014. Eliciting preferences for key attributes of intrapartum care in the Netherlands. Birth [online]. 41(2), pp.185-194. [viewed 30 June 2016]. Available from:

http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com.gcu.idm.oclc.org/doi/10.1111/birt.12081/epdf

Haith-Cooper, M., & Bradshaw, G., 2013. Meeting the health and social needs of pregnant asylum seekers. midwifery students’ perspectives Nurse Education Today [online]. 33(9), pp. 1008 – 1013. [viewed 30 June 2016]. Available at:

http://su3pq4eq3l.search.serialssolutions.com/?ctx_ver=Z39.88-2004&ctx_enc=info%3Aofi%2Fenc%3AUTF-8&rfr_id=info%3Asid%2Fsummon.serialssolutions.com&rft_val_fmt=info%3Aofi%2Ffmt%3Akev%3Amtx%3Ajournal&rft.genre=article&rft.atitle=Meeting+the+health+and+social+care+needs+of+pregnant+asylum+seekers%3B+midwifery+students%27+perspectives%3A+Part+3%3B+%22The+pregnant+woman+within+the+global+context%22%3B+an+inclusive+model+for+midwifery+education+to+address+the+needs+of+asylum+seeking+women+in+the+UK&rft.jtitle=Nurse+Education+Today&rft.au=Melanie+Haith-Cooper&rft.au=Gwendolen+Bradshaw&rft.date=2013-09-01&rft.pub=Elsevier+Science+Ltd&rft.issn=0260-6917&rft.eissn=1532-2793&rft.volume=33&rft.issue=9&rft.spage=1045&rft.externalDocID=3067339971¶mdict=en-US].

Hanegem, van, N., Miltenburg, A. S., Zwart, J. J., Bloemenkamp, K. W.M. & Roosmalen, van J., 2011. “Severe acute maternal morbidity in asylum seekers: a two-year nationwide cohort study in the Netherlands”. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica [online]. 90(9), pp.1010–1016. [viewed 28 November 2014]. Available at:

http://su3pq4eq3l.search.serialssolutions.com/?ctx_ver=Z39.88-2004&ctx_enc=info%3Aofi%2Fenc%3AUTF-8&rfr_id=info:sid/summon.serialssolutions.com&rft_val_fmt=info:ofi/fmt:kev:mtx:journal&rft.genre=article&rft.atitle=Severe+acute+maternal+morbidity+in+asylum+seekers%3A+a+two-year+nationwide+cohort+study+in+the+Netherlands&rft.jtitle=Acta+obstetricia+et+gynecologica+Scandinavica&rft.au=Van+Hanegem%2C+Nehalennia&rft.au=Miltenburg%2C+Andrea+Solnes&rft.au=Zwart%2C+Joost+J&rft.au=Bloemenkamp%2C+Kitty+W+M&rft.date=2011-09-01&rft.eissn=1600-0412&rft.volume=90&rft.issue=9&rft.spage=1010&rft_id=info:pmid/21446931&rft.externalDocID=21446931¶mdict=en-US

Hayes, I., Enohumah, K & McCaul, C., 2011. Care of the migrant obstetric population. International Journal of Obstetric Anesthesia [online]. 20(4) pp. 321–329. [viewed 07 June 2016]. Available at: http://www.sciencedirect.com.gcu.idm.oclc.org/science/article/pii/S0959289X11000720

Hesselink, A. E. & Harting, J., 2011. Process evaluation of a multiple risk factor perinatal programme for a hard-to-reach minority group: Process evaluation of a multiple risk factor perinatal programme. Journal of Advanced Nursing [online]. 67(9), pp. 2026-2037. [viewed 30 June 2016]. Available from: http://su3pq4eq3l.search.serialssolutions.com/?ctx_ver=Z39.88-2004&ctx_enc=info%3Aofi%2Fenc%3AUTF-8&rfr_id=info%3Asid%2Fsummon.serialssolutions.com&rft_val_fmt=info%3Aofi%2Ffmt%3Akev%3Amtx%3Ajournal&rft.genre=article&rft.atitle=Process+evaluation+of+a+multiple+risk+factor+perinatal+programme+for+a+hard-toreach+minority+group&rft.jtitle=Journal+of+Advanced+Nursing&rft.au=Hesselink%2C+Arlette+E&rft.au=Harting%2C+Janneke&rft.date=2011-04-01&rft.issn=0309-2402&rft.eissn=13652648&rft.spage=no&rft.epage=no&rft_id=info:doi/10.1111%2Fj.1365-2648.2011.05644.x&rft.externalDBID=n%2Fa&rft.externalDocID=10_1111_j_1365_2648_2011_05644_x¶mdict=en-US

Holloway, I., 2001. Revisiting qualitative inquiry: Interviewing in nursing and midwifery research. Journal of Research in Nursing, 6(1), pp. 539-550. [viewed 30 June 2016]. Available from: http://jrn.sagepub.com.gcu.idm.oclc.org/content/6/1/539.full.pdf+html

Jans, S., Perdok, H., Dillen, J. v., Jonge, A. d., Verhoeven, C., & Mol, B. W., 2015. Intrapartum referral from primary to secondary care in the netherlands: A retrospective cohort study on management of labor and outcomes. Birth-Issues in Perinatal Care [online]. 42(2), pp.156-164. [viewed 30 June 2016]. Available from:

http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com.gcu.idm.oclc.org/doi/10.1111/birt.12160/epdf

Johnson-Agbakwu, C. E., Allen, J., Nizigiyimana, J. F., Ramirez, G. & Hollifield, M., 2014. Mental health screening among newly arrived refugees seeking routine obstetric and gynecologic care. Psychological Services [online]. 11(4), pp. 470-476. [viewed 25 June 2016]. Available at:

http://search.proquest.com.gcu.idm.oclc.org/docview/1622610094?pq-origsite=summon

Jonge, de A., Baron, R., Westerneng, M., Twisk, J. & Hutton, E. K., 2013. Perinatal mortality rate in the Netherlands compared to other european countries: A secondary analysis of euro-PERISTAT data. Midwifery [online], 29(8). [viewed 30 June 2016]. Available from:

http://su3pq4eq3l.search.serialssolutions.com/?ctx_ver=Z39.88-2004&ctx_enc=info%3Aofi%2Fenc%3AUTF-8&rfr_id=info%3Asid%2Fsummon.serialssolutions.com&rft_val_fmt=info%3Aofi%2Ffmt%3Akev%3Amtx%3Ajournal&rft.genre=article&rft.atitle=Perinatal+mortality+rate+in+the+Netherlands+compared+to+other+European+countries%3A+A+secondary+analysis+of+Euro-PERISTAT+data&rft.jtitle=Midwifery&rft.au=De+Jonge%2C+Ank&rft.au=Baron%2C+Ruth&rft.au=Westerneng%2C+Myrte&rft.au=Twisk%2C+Jos&rft.date=2013-08-01&rft.pub=Elsevier+B.V&rft.issn=0266-6138&rft.eissn=1532-3099&rft.volume=29&rft.issue=8&rft.spage=1011&rft_id=info:doi/10.1016%2Fj.midw.2013.02.005&rft.externalDBID=BSHEE&rft.externalDocID=336416914¶mdict=en-US

Kandasamy, T., Cherniak, R., Shah, R., Yudin, M.H., Spitzer, R., 2014. Obstetric Risks and Outcomes of Refugee Women at a Single Centre in Toronto. J Obstet Gynaecol Can [online]. 36(4), pp. 296-302. [viewed 25 June 2016]. Available at: http://comingsoon.jogc.com/article/S1701-2163(15)30604-6/pdf

Krainovich-Miller, B., Haber, J., Yost, J. & Jacobs, S.K., 2009. “Evidence-Based Practice Challenge: Teaching Critical Appraisal of Systematic Reviews and Clinical Practice Guidelines to Graduate Students”. Journal of Nursing Education [online]. 48(4), pp. 186-95. [viewed 28 November 2014]. Available at:

http://search.proquest.com.gcu.idm.oclc.org/docview/203935334?pq-origsite=summon#center

Kurth, E., Jaeger, F. N., Zemp, E.T., schudin, S. & Bischoff, A., 2010. “Reproductive health care for asylum-seeking women – a challenge for health professionals”. BMC Public Health [online]. 10, pp. 659. [viewed 31 October 2014]. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2988736/

Kvernbekk, T., 2011. “The concept of evidence in evidence-based practice”, Educational Theory [online]. 61(5), pp. 515-532. [viewed 28 November 2014]. Available at: http://search.proquest.com.gcu.idm.oclc.org/docview/896731921?pq-origsite=summon

Lawless, A., Freeman, T., Bentley, M., Baum, F. & Jolley, C., 2014. “Developing a good practice model to evaluate the effectiveness of comprehensive primary health care in local communities”. BMC Family Practice [online]. 15(1), pp. 9. [viewed 13 November 2014]. Available at: http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2296/15/99

Leaning, J., Spiegel, P. & Crisp, J. 2011. Public health equity in refugee situations. Conflict and Health [online]. 5(6). [viewed 17 June 2016]. Available at: http://conflictandhealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1752-1505-5-6

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3117691/pdf/1752-1505-5-6.pdf

Medical Ethics Review Committee MRECs: CCMO, MRECs, 2014. [online]. [viewed 6 December 2014]. Available at: http://www.ccmo.nl/en/accredited-mrecs

3McKibbon, K.A. & Marks, S., 1998. “Searching for the Best Evidence. Part 1: Where to Look”. Evidence-based Nursing [online]. 1(3), pp. 68-70. [viewed 13 November 2014]. Available at: http://ebn.bmj.com/content/1/3/68.full

MCA Menzis COA Administratie MCA, 2015. Overeenkomst Verloskunde 2015 [online]. [viewed 01 December 2015]. Available at:

http://www.rzasielzoekers.nl/dynamic/media/28/documents/voorbeeldcontracten/VERLOSKUNDE.pdf

Merry, L.A., Gagnon, A.J., Kalim, N. & Bouris, S.S., 2011. “Refugee Claimant Women and Barriers to Health and Social Services Post-birth”. Canadian Journal of Public Health [online]. 102(4), pp. 286-90. [viewed 07 November 2014]. Available at:

http://search.proquest.com.gcu.idm.oclc.org/docview/884329235?pq-origsite=summon

Midwifery in the Netherlands Koninklijke Nederlandse Organisatie van Verloskundigen Beroepsorganisatie van en voor verloskundigen KNOV (Midwifery in the Netherlands): GuideLines, 2014. [online]. [Viewed18 December 2015]. Available at: http://www.knov.nl/vakkennis-en-wetenschap/tekstpagina/14/richtlijnen/

Muijsenbergh, van den M., Weel-Baumgarten, van E., Burns. N., O’Donnell, C., Mair, F., Spiegel, W. & MacFarlane, A., 2014. Communication in cross-cultural consultations in primary care in europe: The case for improvement, the rationale for the RESTORE FP 7 project. Primary Health Care Research & Development [online].15(2), pp.122-133. [viewed 25 June 2016]. Available at: http://su3pq4eq3l.search.serialssolutions.com/?ctx_ver=Z39.88-2004&ctx_enc=info%3Aofi%2Fenc%3AUTF-8&rfr_id=info%3Asid%2Fsummon.serialssolutions.com&rft_val_fmt=info%3Aofi%2Ffmt%3Akev%3Amtx%3Ajournal&rft.genre=article&rft.atitle=Communication+in+cross-cultural+consultations+in+primary+care+in+Europe%3A+the+case+for+improvement.+The+rationale+for+the+RESTORE+FP+7+project&rft.jtitle=Primary+Health+Care+Research+%26+Development&rft.au=van+den+Muijsenbergh%2C+Maria&rft.au=van+Weel-Baumgarten%2C+Evelyn&rft.au=Burns%2C+Nicola&rft.au=O%27Donnell%2C+Catherine&rft.date=2014-04-01&rft.issn=1463-4236&rft.eissn=1477-1128&rft.volume=15&rft.issue=2&rft.spage=122&rft.epage=133&rft_id=info:doi/10.1017%2FS1463423613000157&rft.externalDBID=n%2Fa&rft.externalDocID=10_1017_S1463423613000157¶mdict=en-US

Norredam, M., Mygind, A., Krasnik, A., 2006. Access to health care for asylum seekers in the European Union – a comparative study of country policies. Eur J Public Health [online]. 16(3), pp. 286-90. [viewed 17 June 2016]. Available at: http://eurpub.oxfordjournals.org/content/eurpub/16/3/285.full.pdf

NVOG Dutch Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology: Guidelines, viewpoints, model protocols etc., 2014 [online]. [viewed 18 December 2014]. Available at:

http://www.nvog.nl/vakinformatie/Kwaliteitsnormen,+richtlijnen,+standpunten+enz/default.aspx

Oostrum, van E.A., Goosen, S., Uitenbroek, D.G., Koppenaal, H. & Stronks, K., 2011. “ Mortality and causes of death among asylum seekers in the Netherlands, 2002-2005”. J Epidemiol Community Health [online]. 65(4), pp. 376-383. [viewed 28 November 2014]. Available at: jech.bmj.com.gcu.idm.oclc.org/content/65/4/376.full

Pellegrino, E.D., 2005. Some things ought never be done: moral absolutes in clinical ethics. Theoretical Medicine and Bioethics [online]. 26(6), pp. 469–486. [Accessed 18 December 2014]. Available at: http://download.springer.com.gcu.idm.oclc.org/static/pdf/783/art%253A10.1007%252Fs11017-005-2201-2.pdf?auth66=1419879923_e46dedfda77e12a12da8b4382bbe244b&ext=.pdf

Perdok, H., Jans, S., Verhoeven, C., Henneman, L., Wiegers, T., Mol, B.W. & de Jonge, A., 2016. Opinions of maternity care professionals and other stakeholders about integration of maternity care: A qualitative study in the Netherlands. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth [online] 16(1). pp. 188. [viewed 30 June 2016]. Available from: https://bmcpregnancychildbirth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12884-016-0975-z

Polit, D.F. & Beck, C.T., 2010. “Generalization in quantitative and qualitative research: Myths and strategies”. International Journal of Nursing Studies [online]. 47(11), pp. 1451–1458. [Accessed 28 November 2014]. Available at: http://www.sciencedirect.com.gcu.idm.oclc.org/science/article/pii/S0020748910002063

Ramsey, K.W., Davis, J., & French, G., 2012. Perspectives of Chuukese Patients and Their Health Care Providers on the Use of Different Sources of Interpreters. Hawai’i Journal of Medicine & Public Health [online]. 7(9), pp. 249–252. [viewed 07 June 2016]. Available at:

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3443847/pdf/hjmph7109_0249.pdf

Rechel, B., Mladovsky, P., Devillé, W., Rijks, B., Petrova-Benedict, R. & McKee, M., 2011. Migration and health in de European Union [online]. World Health Organization , New York. [viewed 01 June 2016]. Available at: http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0019/161560/e96458.pdf

Rechel, B., Mladovsky, P. & Devillé, W., 2012. Monitoring migrant health in Europe: A narrative review of data collection practices. Health Policy [online]. 105(1), pp. 10-16. [viewed 01 June 2016]. Available at: http://www.sciencedirect.com.gcu.idm.oclc.org/science/article/pii/S0168851012000048

Rees, C., 2011. An introduction to Research for Midwives [online]. 3rd ed. Churchill Livingstone. [viewed 13 November 2014]. Available at: https://www.dawsonera.com/readonline/9780702045929

Reynolds, B.M., & White, J.M.A., 2010. “Seeking asylum and motherhood: health and wellbeing needs”. Community Practitioner [online]. 83(3), pp. 20-3. [viewed 30 June 2016]. Available at:

http://search.proquest.com.gcu.idm.oclc.org/docview/213346080?OpenUrlRefId=info:xri/sid:summon&accountid=15977

Riggs, E., Davis, E., Gibbs, L., Block, K., Szwarc, J., Casey, S. & Waters, E., 2012. Accessing maternal and child health services in melbourne, australia: Reflections from refugee families and service providers. BMC Health Services Researce [online]. 12(1), pp.117-117. [viewed 25 June 2016]. Available at: http://bmchealthservres.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1472-6963-12-117

Ruiz-Casares, M., Cleveland, J., Oulhote, Y., Dunkley-Hickin, C., & Rousseau, C., 2016. Knowledge of Healthcare Coverage for Refugee Claimants: Results from a Survey of Health Service Providers in Montreal. PLoS ONE [online]. 11(1). [viewed 17 June 2016]. Available at:

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4720478/pdf/pone.0146798.pdf .

RZA: Regeling Zorg Asielzoekers, Organisatie Gezondheidszorg Asielzoekers, MZA, 2016. [online]. [viewed 01 June 2016]. Available at: http://www.rzasielzoekers.nl/home/zorg-voor-asielzoekers.html

Rodrigues, E.M, Nascimento, do R.G. & Araújo, A., 2010. Prenatal care protocol: actions and the easy and difficult aspects dealt by Family Health Strategy nurses, 2010. Rev Esc Enferm USP [online]. 45(5). [viewed 17 July 2015]. Available at: http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0080-62342011000500002&lng=en&nrm=iso&tlng=en

Roztocki. N., 2001. Using internet-based surveys for academic research: opportunities and problems. American Society of Engineering [online]. 18, pp. I-II. [ [viewed 7 July 2016]. Available at: http://www2.newpaltz.edu/~roztockn/alabam01.pdf

School of Health and Life Sciences: Glasgow Caledonian University, 2016. [online]. [viewed 7 July 2016]. Available at: http://www.gcu.ac.uk/hls/ethics

Sleptsova, M., Hofer, G., Morina, N. & Langewitz, W., 2014. The Role of the Health Care Interpreter in a Clinical Setting—A Narrative Review, Journal of Community Health Nursing [online]. 31(3), pp. 167-184. [viewed 07 June 2016]. Available at: http://su3pq4eq3l.search.serialssolutions.com/?ctx_ver=Z39.88-2004&ctx_enc=info%3Aofi%2Fenc%3AUTF-8&rfr_id=info%3Asid%2Fsummon.serialssolutions.com&rft_val_fmt=info%3Aofi%2Ffmt%3Akev%3Amtx%3Ajournal&rft.genre=article&rft.atitle=The+role+of+the+health+care+interpreter+in+a+clinical+setting–a+narrative+review&rft.jtitle=Journal+of+community+health+nursing&rft.au=Sleptsova%2C+Marina&rft.au=Hofer%2C+Gertrud&rft.au=Morina%2C+Naser&rft.au=Langewitz%2C+Wolf&rft.date=2014&rft.eissn=1532-7655&rft.volume=31&rft.issue=3&rft.spage=167&rft_id=info%3Apmid%2F25051322&rft.externalDocID=25051322¶mdict=en-US

The Health Care Inspectorate, 2014. Inzet professionele tolken en overdracht bij overplaatsing moeten beter voor verantwoorde geboortezorg aan asielzoekers (professional interpreters and transfer should be better for responsible birth care for asylum seekers) [online]. Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sport, Utrecht, pp.7. [viewed 01 June 2016]. Available at: http://www.igz.nl/zoeken/document.aspx?doc=Inzet+professionele+tolken+en+overdracht+bij+overplaatsing+moeten+beter+voor+verantwoorde+geboortezorg+aan+asielzoekers&docid=6807

Tobin, C., Murphy-Lawless, J. & Beck, C.T., 2014. Childbirth in exile: Asylum seeking women’s experience of childbirth in Ireland. Midwifery [online]. 30(7), pp. 831-838. [viewed 07 June 2016]. Available at: http://www.midwiferyjournal.com/article/S0266-6138(13)00217-9/pdf

Tobin, C. L. & Murphy-Lawless, J., 2014. Irish midwives’ experiences of providing maternity

care to non-Irish women seeking asylum. International Journal of Women’s Health [online]. 6, pp. 159–169. [viewed 07 June 2016]. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3916638/pdf/ijwh-6-159.pdf [Accessed on 7 June 2016]

Troe, E.J., Raat, H. & Jaddoe, V.W., 2007. “Explaining differences in birthweight between ethnic populations: The generation R study”. Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology [online]. 114(12), pp. 1557-1565. [viewed 01 June 2016]. Available at: http://su3pq4eq3l.search.serialssolutions.com/?ctx_ver=Z39.88-2004&ctx_enc=info%3Aofi%2Fenc%3AUTF-8&rfr_id=info:sid/summon.serialssolutions.com&rft_val_fmt=info:ofi/fmt:kev:mtx:journal&rft.genre=article&rft.atitle=Explaining+differences+in+birthweight+between+ethnic+populations.+The+Generation+R+Study&rft.jtitle=BJOG+%3A+an+international+journal+of+obstetrics+and+gynaecology&rft.au=Troe%2C+E+J+W+M&rft.au=Raat%2C+H&rft.au=Jaddoe%2C+V+W+V&rft.au=Hofman%2C+A&rft.date=2007-12-01&rft.eissn=1471-0528&rft.volume=114&rft.issue=12&rft.spage=1557&rft_id=info:pmid/17903227&rft.externalDocID=17903227¶mdict=en-US

UNHCR The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees: Statistical Online Population Database, 2016 [online]. [viewed 2 July 2016]. Available at: http://www.unhcr.org/en-us/statistics/country/45c06c662/unhcr-statistical-online-population-database-sources-methods-data-considerations.html

UNHCR United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees: Asylum Levels and Trends in Industrialized Countries, 2016 [online]. [viewed 02 July 2016]. Available at: http://www.unhcr.org/pages/49c3646c137.html

World Health Organization WHO, Declaration of Alma-Ata, International Conference on Primary Health Care, 1978.“ USSR, 6–12” [online]. WHO. [viewed 29 November 2014]. Available at: http://www.who.int/publications/almaata_declaration_en.pdf?ua=1

World Medical Association: The World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: 1964-2014 – 50 years of evolution of medical research ethics, 2014 [online]. [viewed 29 November 2014]. Available at: http://www.wma.net/en/30publications/32doh/index.html

Yelland, J., Riggs, E., Szwarc, J., Casey, S., Dawson, W., Vanpraag, D. & Brown, S., 2015. Bridging the Gap: using an interrupted time series design to evaluate systems reform addressing refugee maternal and child health inequalities. Implementation Scienc [online]. 10, pp. 62. [viewed 25 June 2016]. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4425879/pdf/13012_2015_Article_251.pdf.